The San Francisco Chronicle Reports that a condo listing at 2701 Van Ness Ave #604 is offering a year of unlimited Uber rides in lieu of a parking spot. Embracing the “sharing economy”, wily realtors are expected to offer free unlimited bottled water delivery from Google Express for listed properties without functional plumbing.

Airbnb Pays Hotel Tax to the City of San Francisco

SFist reports that Airbnb recently paid an undisclosed amount (believed to be $25 million) to the City of San Francisco for an assessed “hotel tax”. San Francisco recently passed an “Airbnb legitimacy law” (available here), allowing tenants to participate in the sharing economy as long as they follow the rules of the regulation (including limitations on number of days per year, registration with the Planning Department, carrying insurance, etc). A proposed amendment – requiring that Airbnb pay back taxes – failed to pass, but Airbnb nonetheless made good on the assessment.

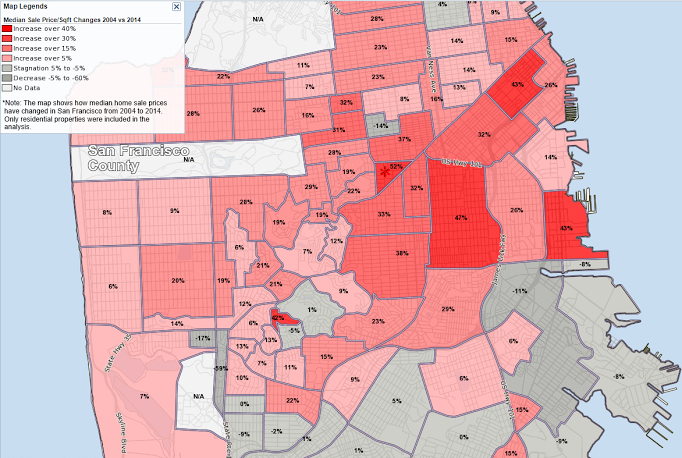

A Decade of Real Estate Price Changes in San Francisco

PropertyShark.com put together an interesting map of changes in San Francisco median home prices, by neighborhood, over the past decade. Zoom in for changes in price per square foot. Surprisingly, some neighborhoods dropped in price (presumably within a wide margin of error).

San Francisco Rent Board Clarifies Position on Effective Date of New Buy-Out Agreement Compliance Requirements, Effective March 7, 2015

The San Francisco Rent Board recently clarified their position on when the new Buy-Out negotiation disclosure statements must be obtained from tenants and when they must be filed. That information is copied below and available on the Rent Board website here.

It is important to note that, even if the negotiations begin prior to March 7, 2015, such that the landlord is not required to obtain a signed disclosure form, the actual buy-out agreement must still be filed with the Rent Board if the agreement is executed after March 7, 2015.

—

New Ordinance Amendment Regulating Buyout Agreements

Rent Ordinance Section 37.9E, effective March 7, 2015, is a new provision that regulates “buyout agreements” between landlords and tenants under which landlords pay tenants money or other consideration to vacate their rent-controlled rental units. An agreement to settle a pending unlawful detainer action does not constitute a “buyout agreement” for purposes of Section 37.9E.

Starting March 7, 2015, Section 37.9E requires landlords to provide tenants with a Rent Board-approved Disclosure Form and to file a Rent Board-approved Notification Form with the Rent Board before beginning buyout negotiations. The Rent Board will make this information publicly available (except for information regarding the identity of the tenants). Section 37.9E also requires that all buyout agreements be in writing and contain certain disclosures, including a tenant’s right to rescind the agreement within 45 days of execution. For buyout agreements executed on or after March 7, 2015, the new law requires the landlord to file a copy of the buyout agreement with the Rent Board within 46 to 59 days after execution. The Rent Board will post all such buyout agreements in a searchable database that is available to the public at the Rent Board’s office. Before posting a copy of a buyout agreement on its database, the Rent Board will redact all information regarding the identity of the tenants.

If a landlord begins buyout negotiations before March 7, 2015, but those negotiations result in a buyout agreement executed after March 7, 2015, the Disclosure and Notification Forms are not required, but the buyout agreement must still be filed with the Rent Board. Any dispute about when buyout negotiations began must be resolved in court and not at the Rent Board.

Section 37.9E also specifies various remedies and penalties against a landlord for violation of the above requirements that can be enforced in a civil action in state court. In addition, Subdivision Code Section 1396(e)(4) was amended to provide that buyout agreements with certain tenants after October 31, 2014 shall be the basis to deny an application for condominium conversion of the building.

A copy of Ordinance No. 225-14 amending Rent Ordinance Section 37.9E and Subdivision Code 1396 is provided here for your convenience.

Will Mosser Companies v. City and County of San Francisco Prompt Another Amendment to Costa-Hawkins?

“Whether the application of rent control protection to occupants who begin their residency as minors is wise economic policy is a question for legislative, not judicial, determination.”

The First Appellate District recently determined the effect of Costa-Hawkins on a tenancy where the only parties to a lease have moved, leaving behind their son, who entered the rental unit, as a minor, and who became an adult during his parents’ occupancy.

In Mosser Co. v. City and County of San Francisco, the Court held that the son was an “original occupant”, having moved in at the commencement of the tenancy and with the consent of the landlord, even though he was not a party to the lease. It followed that the decontrol provisions of Costa-Hawkins would not allow the establishment of a new rental rate while an “original occupant” was still in possession.

This is a difficult decision. The court began its analysis with the uncontroversial proposition that an “occupant” is someone who can claim a right of “possession” in a rental unit, and that such an occupant may be considered an “original occupant”, even where they are not a party to the lease, so long as they took possession at the commencement of the tenancy with knowledge of the landlord.

This is a fair interpretation of Costa-Hawkins, as applied to the Rent Ordinance, and it is rooted in well-established law, predating Costa-Hawkins. (The Mosser court referred to Parkmerced Co. v. San Francisco Rent Stabilization & Arbitration Bd. (1989) 215 Cal.App.3d 490, 495, for the rule that “[o]ne may become a tenant at will or a periodic tenant under an invalid lease, or without any lease at all, by occupancy with consent”.) And this rule would avoid, for instance, a landlord renting a three room unit to three people, but only entering a written contract with one of them, in an effort to game the decontrol provisions if that single person ever left. (The other two would obviously be “original occupants”, who would be no less obligated to honor the original lease provisions or entitled to receive the benefit of them.)

However, in allowing an inter-generational, rent-controlled tenancy, the Mosser court may have taken this rule beyond any reasonable construction. The court effectively found that the son had the same rights as any other adult, who might have moved in at the commencement of the tenancy.

This logic glosses over the fact that a landlord may not want, e.g., three or more adults to move into a one-bedroom apartment, and may limit the number of occupants on the lease accordingly, but that this landlord may not (and probably should not) object to a space-appropriate number of adults moving in with their children.

It also gives the son all of the benefits of legal capacity, without any of its obligations, until such time as he may unilaterally elect to secure a rent-controlled tenancy at sub-market rates in the future. The court was not persuaded by the landlord’s argument that it was allowing the son to “inherit” the rent-controlled tenancy and receive rights without concomitant obligations. It nonetheless held that the son has his own personal right of occupancy.

But what would happen if the parents vacated, and the son remained behind while he was still a minor? By the court’s application of Parkmerced Co., the right could not become a tenancy by operation of law, because a minor is incapable of contracting generally (Cal. Civ., §§1556, 1557), and, in particular, incapable of entering “a contract relating to real property or an interest therein”. (Cal. Fam., §6701(b).)

In that event, the son has no “concomitant obligations” that offset the rights given to him by the court. It seems, therefore, inescapable, that the son only enjoyed these rights by virtue of becoming an adult. Now, of course, this is not the same thing as “inheriting” (at least in the legal sense), but the court took a snapshot of his rights in the present (now that he’s an adult) and retroactively applied them to the minor child, at the inception of the tenancy, where they could not possibly manifest.

The court bolstered its policy determination by warding off concerns that this would allow an occupant to indefinitely parlay a rent-controlled tenancy indefinitely. “[T]he protection afforded here is limited in scope to lawful and original occupants. A rent-controlled apartment cannot, as landlord fears, be passed on freely ‘from friend to friend or generation to generation.’ Only those occupants who reside in the apartment at the start of the tenancy and do so with the landlord’s express or implicit consent are protected from unregulated rent increases.”

However, the court also says that the son – an occupant, despite not being a party to the original lease, who became a tenant by “occupation and consent” – will be creating a tenancy of his own, now that his parents are vacated and the landlord still needs to collect rent.

This establishes a new tenancy. Presumably, now that the rest of the family is gone, the son has roommates. Are these occupants? Yes. Are they occupants who took possession under the (now newly “original”) lease? Yes. Can the landlord do anything other than consent to their occupancy, now that he has no choice but to accept rent from the son or let him live there for free…

Despite its airs of judicial self-restraint, the Mosser court made a public policy choice here, and this may have undesired consequences to landlord-tenant relationships in rent-controlled jurisdictions, unless the California Legislature takes the court up on its invitation to amend Costa-Hawkins.

Mayor Lee Proposes Comprehensive Housing Bond To Help Middle Class

The San Francisco Business Times reports that Mayor Ed Lee has proposed a $250 million general obligation bond to pay for new construction, which he will present to the voters this November, noting the last time the City passed a housing bond was in 1996. The bond would allocate funds to help middle class residents.

San Francisco Legislative Updates for 2015: Regulation of Tenant Buyout Agreements

Ordinance 225-14 becomes operative on April 6, 2015. It adds section 37.9E to the Rent Ordinance, and it imposes onerous requirements to the conduct of an owner/landlord who wishes to negotiate for a “buy-out” with their tenants. Some of these requirements even apply prior to the commencement of negotiations.

The Rent Board will create a form with some required information that a landlord needs to provide a tenant prior to commencing negotiations. The form includes a dated signature from the tenant, indicating when they received the disclosure. Then – and still prior to “negotiating” – the landlord has to file a form with the Rent Board with some biographical information about the landlord, tenant and property and an affidavit that the tenants received the form.

Then… the landlord can start negotiating. The actual agreement must be in writing, and it must include several specific statements – the lack of any of which will allow the tenant to rescind the agreement at any time! And, even if all of those statements are included, the tenants may rescind for up to 45 days after execution.

Buy-out agreements must also be filed with the Rent Board, after the tenant’s right to rescind has expired, but no later than 59 days after execution (i.e., there’s a two week window).

This also requires the Rent Board to make a searcheable database of buyout agreements. So, this is probably headed toward creating an “MLS of buy-outs” to equip tenants with better information for fetching the highest price for their rent controlled tenancies.

This section creates civil liability and provides an attorneys’ fee provision for tenants in suing landlords who haven’t complied with the requirements, and it has a four year statute of limitations.

It also imposes strict limitations in the condo conversion lottery. This will add language to section 1396 of the Subdivision Code preventing conversion if the owner has bought out a single elderly or disabled tenant, or if they’ve bought out any two tenants within ten years of final map approval.

Legislative language available here.

San Francisco Legislative Update for 2015: Amending Regulation of Short-Term Residential Rentals and Establishing Fee

Ordinance 218-14 will become operative on February 1, 2015. It is a big piece of a broader effort by San Francisco to regulate AirBnb, VRBO and other hosting platforms in the increasingly popular “sharing economy”. The changes impact the eviction provisions of the Rent Ordinance, as well as the interpretation of this kind of use within the Residential Unit Conversion Ordinance. The short version is that owners may not offer rental units on hosting platforms, and tenants might be able to, under certain conditions.

In order to comply, a tenant has to register the unit with the new Planning Department registry for keeping track of transient use. They have to obtain insurance and a business license, pay the transient occupancy tax. They must occupy the unit for at least 275 days out of the year (or 75% of a prorated year), and they cannot profit off the “subletting” (to the extent they are subject to the rent-control provisions of Section 37.3 of the Rent Ordinance).

This new exception expressly does not supersede restrictions against housing platform listings in CC&Rs, leases or TIC agreements, so, as with many landlord-tenant issues, the first place to check for authorization is the lease agreement itself.

The biggest change for landlords is probably the new language in Rent Ordinance Section 37.9(a)(4): “The tenant is using or permitting a rental unit to be used for any illegal purpose, provided however that a landlord shall not endeavor to recover possession of a rental unit solely as a result of a first violation of Chapter 41A that has been cured within 30 days written notice to the tenant.” (New language in bold.)

Legislative language available here.

San Francisco Legislative Update for 2015: Campos Amendment relocation assistance on Ellis Act Evictions

Ordinance 54-14 amended the Rent Ordinance to increase relocation assistance to two years worth of rent payment differential between the existing unit and a comparable unit. At the moment, this has been found unconstitutional (see, Jacoby, et al. v. CCSF, San Francisco Superior Court Case No. CGC-14-540709, and Levin v. CCSF, Federal District Court case no. 3:14-cv-03352), but the City is appealing the decision. Keep checking Costa-Hawkins.com for updates.

Legislative language available here.

San Francisco Legislative Update for 2015: “Authorization of Dwelling Units Constructed Without a Permit in an Existing Building Zoned for Residential Use”

Ordinance 43-14 became effective May 7, 2014. It allows an owner of a building with an illegal “in-law” unit (one built without a permit), which was built before January 1, 2013, to apply to the Building Department for a permit to legalize it.

The owner may not legalize the in law unit where they have evicted a tenant under section 37.9(a)(8) of the Rent Ordinance (“owner move-in” eviction) within five years or under any of the other non-fault eviction provisions within ten years (with an exception for capital improvement evictions if the tenant received an offer to re-rent and/or actually moved back in). The owner may not pass costs of conversion through to the tenant. And the new unit is not eligible for condo conversion.

Legislative language available here.